The safety case for electromechanical actuators over hydraulic cylinders

Linear motion machine designers are increasingly specifying electromechanical actuators because they are cleaner, easier to control, and require less maintenance than hydraulic cylinders. Often overlooked, however, are the many intrinsic safety benefits that come with using electromechanical solutions. These are derived from eliminating the need for hydraulic fluid and implementing an all-electric load handling solution.

Safety risks of: hydraulic cylinder-based motion control

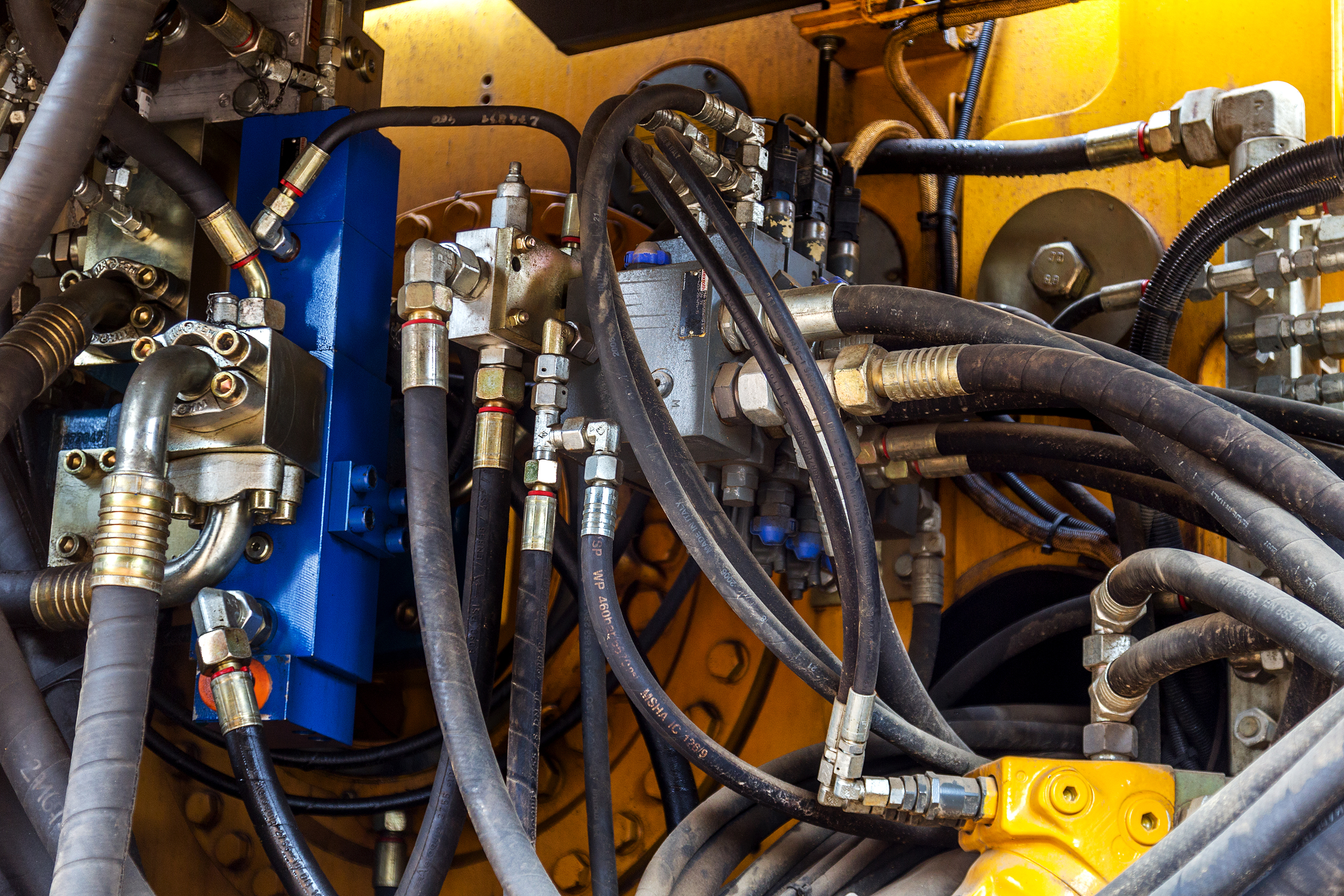

Design engineers specify hydraulic cylinders for their high-strength, high-cycle operation, but achieving this requires an intricate external system of hoses, connectors, filters, switches, valves and pumps. (Figure 1) Even a small hydraulic system (2,000-5,000 psi) could have at least eight separate moving parts, but some can be pressurized up to 10,000 psi and heated to 180 degrees F.

Figure 1: Hydraulic systems can be complicated due to the requirement of multiple hoses, connectors, valves, filters and switches to operate. (Image: Thomson Industries)

These factors, combined with the inherent characteristics of hydraulic oil , can result in any of the following problems:

- Physical trauma. High-temperature, high-pressure systems present potential risk even in routine operation, but as these wear and components fail, the risk of danger increases. Close proximity to hydraulic lines can potentially result in burns, bruises, cuts, or abrasions from hydraulic lines.

- Exposure risk. The U.S Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry reports that some types of hydraulic fluids can irritate skin or eyes and that ingesting certain types can cause pneumonia, intestinal bleeding, or death in humans.

The effects of breathing air with high levels of hydraulic fluids are not known, but some countries have set hydraulic fluid exposure limits. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommends an exposure limit of 350 mg/m3 of petroleum distillates for a 10-hour workday and 40-hour workweek. - Contamination. In addition to being potentially toxic to humans, hydraulic fluids can be harmful to the environment. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), for example, includes hydraulic fluids on its list of oils that require special handling.

- Slip and fall hazard. There are many reported cases of workers who have been injured by slipping on puddles of leaked fluid or falling while climbing up onto their machines with oil on their hands or shoes.

- Cleanup. Indoor spills may also be subject to local regulation or require additional investment in absorbent substances or other cleanup services.

- Combustibility. Petroleum-based hydraulic fluids are less flammable than petroleum middle distillate fuels such as jet fuel, kerosene or diesel fuel. These can, however, be a fire hazard if sprayed, as might happen when high-pressure leaks convert the fluid to an aerosol state.

Because hydraulic fluids degrade and lose effectiveness over time, they must be replaced regularly, which results in additional cost to maintain an inventory of new oil and filters. Typically, additional maintenance department resources are needed to coordinate the checking of filters and oil integrity to determine when to change the fluids. Laxity in any of these efforts increases the risk of using hydraulic fluids.

The safe choice

Despite such disadvantages as those described above, hydraulic designs have been implemented because they were the best alternative for heavy duty, high-cycle actuation. Hydraulic applications have traditionally been known to handle heavier force and loads in applications for less initial investment. As electromechanical actuators have advanced in capabilities to handle heavier loads, actuator synchronization, and simple implementation – all without hydraulic fluids or intricate plumbing – they deliver comparable or better performance than hydraulic systems.

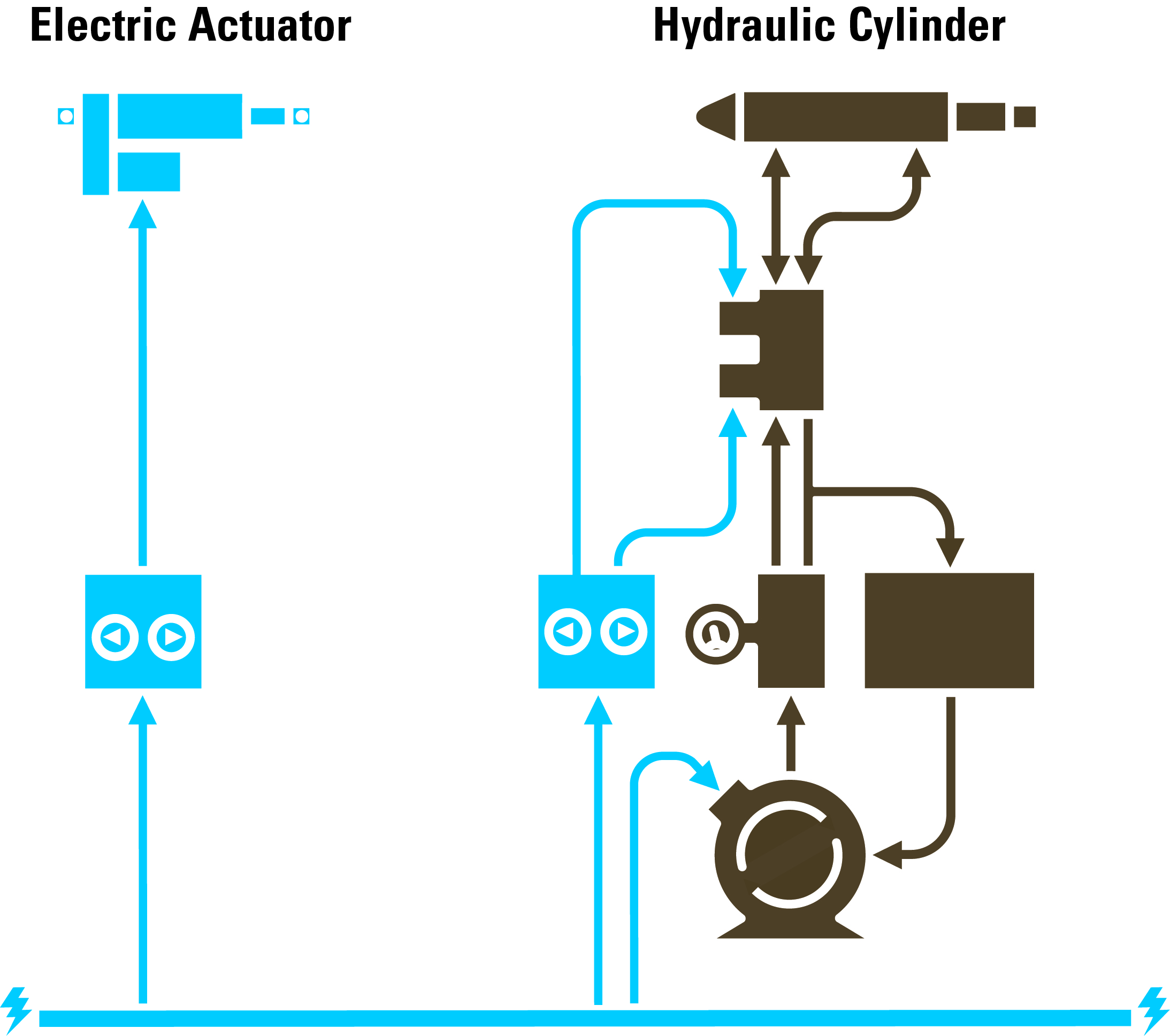

Figure 2: Detailed illustration comparing electric actuators and hydraulic systems. (Image: Thomson Industries)

Figure 2 compares the operation of electric actuators and hydraulic cylinders. Electromechanical actuators embed all operating functionality in the actuator housing itself, which connects an electronic control unit (ECU) with only a few wires. Enabling this capability are built-in microprocessors that can be programmed to report position, provide diagnostic feedback that improves performance, and handle complex functions like synchronizing multiple actuators. In addition to eliminating the hazards related directly to the use of fluids, electromechanical actuators deliver the following plant safety benefits:

- By enabling operators to ramp up speed, slow it down, follow a consistent motion profile or hold a position, electromechanical actuators give them maximum control over the load.

- Compact housings are easier to seal, thus eliminating contamination risks. • Fewer moving parts means less wear and tear and lower risk of failure.

- Implementation and operation of performance monitoring is much easier because most of it is accomplished with software rather than external systems.

- Electronic actuators can accept commands and, in return, provide safety-related data such as load or temperature.

- Operations can be shut down easily in case of an incident. • Electronic systems can be overridden manually if necessary.

- Operation is silent, removing the danger of hearing impairment for those who are constantly exposed to it.

As attention to workplace safety grows among government regulators and the general public, it has become an important consideration when designing for a green motion control solution. Electromechanical actuators address some of the safety disadvantages of hydraulic-cylinder-based systems. Combine this with their ease of operation and maintenance and you have an ideal option for your actuator needs in the future.

Figure 3: Electromechanical actuators are safer than hydraulic-cylinder-based systems because they don’t rely on hazardous fluids and also provide greater control over motion profiles. (Image: Thomson Industries)

1 Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service in Atlanta, GA. Toxicological Profile for Hydraulic Fluids (1997). Retrieved at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxfaqs/tf.asp?id-757&tid=141

2,4 Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service in Atlanta, GA. Toxicological Profile for Hydraulic Fluids (1997). Retrieved at: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxfaqs/tfacts99.pdf

3 Joseph Hrinik (2007) Hydraulic Fluid Hazards. Retrieved at: https://www.forkliftaction.com/news/newsdisplay.aspz?nwid=4584

5 George W. Mushrush, Heather D. Willauer, Jean L. Bailey, John B. Hoover & Frederick W. Williams (2006) Petroleum-Based Hydraulic Fluids and Flammability, Petroleum Science and Technology, 24:12, 1441-1446, Retrieved at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1081/LFT-200056782

6 W.D. Phillips (2006) The High-Temperature degradation of hydraulic oils and fluids. Retrieved at: https://www.hyprofiltration.com/clientuploads/directory/Knowledge/PDFs/High%20Temp%20Degradation%20of%20Hydraulic%20Oils%20%20Fluids.pdf